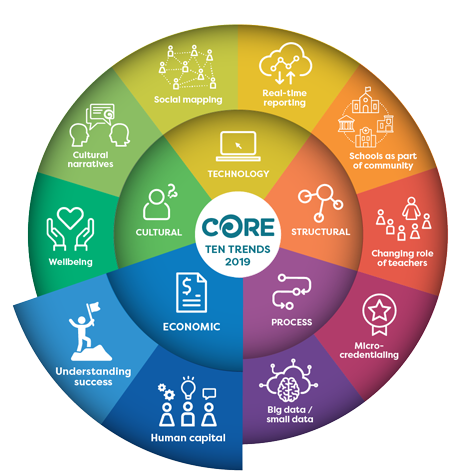

Human capital

What’s this all about?

The concept of human capital has been around for some time. It emerged in economic writing to recognise the fact that people are viewed as crucial to an organisation’s performance, rather than simply as workers who carry out set routines and activities. Economists regard expenditure on education, training, medical care, and so on as investments in human capital.

Including human capital in this list of trends stems from thinking about a future for our young people where they are more than just ‘work ready’ but they also understand what it means to ‘be human’. This includes embracing the responsibilities we have, individually and collectively, to contribute as citizens to building a better world for all. It goes beyond developing the ability to create wealth, in a traditional sense, to considering the impact of this activity on the environment and our fellow citizens.

According to the World Bank (2018) human capital consists of the knowledge, skills, and health that people accumulate throughout their lives, enabling them to realise their potential as productive members of society. Having a comprehensive, good quality education is an important part of this, but so too is the need to consider other aspects such as health and wellbeing.

Being a productive member of society often implies being equipped to contribute to the world of work. Many jobs today, and many more in the near future, will require specific skills, including a combination of technological know-how, problem-solving, and critical thinking as well as competencies such as perseverance, collaboration, and empathy. The changing nature of work makes it difficult to know exactly what we ought to be preparing people for, or how we should be doing that.

We can no longer sustain a ‘front loading’ approach to preparing for the future, instead we must keep learning and changing to acquire skills and dispositions that meet the needs of different contexts and emerging opportunities. The days of staying in one job, or with one company, for decades are waning. In the future workers will likely have many jobs and roles over the course of their careers, which means they will have to be lifelong learners.

The implications of this perspective for kaiako, teachers and education leaders will be seen in what happens in our educational institutions, most noticeably in the curriculum shifts from knowledge acquisition to building global competencies for example. It will also be seen in the move to a greater degree of collaborative activity within and between our institutions, as human capital is best measured in the collective sense rather than in individuals.

What’s driving this change?

There are several factors driving this change, including:

- Personalised learning

- Worker health

- Nature of work

- Technology

Personalising learning

The traditional model of education, born out of the industrial age with a one-size-fits-all approach, does not meet the needs of our knowledge economy. We can do much more to give the next generation a personalised educational experience that equips them with the skills, values, characteristics, and knowledge they need to thrive in contemporary society.

The increased focus on learner-centred approaches and personalised learning initiatives in our education system is indicative of the change driver here. This extends beyond increasing the capabilities of individuals, to understanding the human capital potential that exists within and across the group.

Worker health

Concerns about worker health and safety used to focus almost exclusively on the physical aspects of exercise and diet, together with how best to avoid physical injury at work. After all, a fit and healthy workforce provides maximum return on investment! While these things are still important, contemporary workplace wellness programmes also cover mental, emotional and spiritual aspects. Many programmes are multi-faceted, encompassing areas such as energy management, financial wellbeing, altruism, life-work balance, and connecting with passion and purpose.

Nature of work

As society becomes more complex, and the notion of ‘work/employment’ no longer means a ‘job for life’, we need to think more critically about what it means to be a citizen, and how we might contribute to society in ways that aren’t tied specifically to the traditional idea of ‘work’. When organisations or countries invest in their people, it increases the opportunity for people to reach their own potential, look after their families, and ultimately help their community to grow and prosper.

Technology

Technology has varying impacts on skills and the demand for them in the labour market. It also creates opportunities for us to participate more broadly in society. Organisations and governments across the world are recognising these opportunities, and paving the way to create new jobs, increase productivity, and deliver effective public services. Organisations can grow rapidly thanks to digital transformation, expanding their boundaries and reshaping traditional production patterns. Depending on the technology some skills, and the workers who have them, are gaining greater relevance. Advanced skills like innovation, complex problem-solving and critical thinking are sought after in labour markets. People with these skills can work more effectively with new technologies. Socio-behavioural skills like empathy, teamwork, and conflict resolution are also becoming more valued because they cannot be easily replicated by machines.

What examples of this can I see?

Many examples of this trend are emerging, from local organisations and communities through to the work of governments and global agencies.

At a global level the World Bank has recently released its Human Capital Index (HCI) which measures the amount of human capital that a child born today can expect to attain by age 18. The HCI conveys the productivity of the next generation of workers compared to a benchmark of complete education and full health. It has been constructed for 157 countries (including New Zealand) and is made up of five indicators: the probability of survival to age five, a child’s expected years of schooling, harmonised test scores as a measure of quality of learning, adult survival rate (fraction of 15-year olds that will survive to age 60), and the proportion of children who are not stunted to develop high-order cognitive and socio-behavioural skills.

At a local level companies and educational institutions are becoming increasingly aware of the value of the human capital of its employees and are making strategic decisions to invest in developing this further. For instance, schools / kura that provide mentoring programs for staff at every stage of their career, illustrate that they care about staff development now, and into the future. Professional development programmes tied to a career growth plan is another way to renew and develop human capital. Traditionally schools have left that responsibility to the individual staff member which tends to result in them looking for options outside the school to grow and learn. Linking professional development to an organisation’s strategic intent benefits both the individual and the organisation.

Responses to the changing nature of work, brought about by developments in technology, can be seen in the Digital Technologies and Hangarau Matihiko curriculum content released last year in New Zealand. This is a direct response to the demands from industry groups to increase the human capital of New Zealanders in terms of the range of skills and competencies involved in working with digital technologies. It is a reflection of what is happening at a wider level through the work of organisations such as NZtech and the NZ Tech Alliance.

Alongside this emphasis on specialist skill and knowledge development is the focus that many organisations now place on the wellbeing of staff. Groups and initiatives such as Wellplace, Wellbeing for Health, Workplace Wellbeing, NZ Institute of Wellbeing and Resilience together with the Mental Health Foundation recognise the importance of personal wellbeing in relation to building human capital.

How might we respond?

For us to thrive as individuals, and for society as a whole to thrive, we must ensure our vision of human capital embraces all dimensions of what it means to be human, and focus beyond seeing human capital in terms of job skills and competencies.

Consider the following as starting points for thinking about how you’re addressing the issues around human capital in your context:

- How are you engaging with your staff, students/ākonga whānau and wider community in discussions around the future of work, and the impact this has on your decision making about what is important to learn, and how it is important to learn? How is this translating into decisions about curriculum in your context? What is being assessed and how is it being evaluated?

- How are your staff, students, whānau and wider community addressing the complex issues around the impact of technology in society, and the need for everyone to achieve a high level of digital fluency to function well into the future? What programmes are you providing for teachers/ kaiako and students? How are you ensuring these allow for development beyond simple skill acquisition?

- According to the World Bank HCI data (click on the interactive map of New Zealand) New Zealand children are at school for 13.6 years, but when years of schooling are adjusted for quality of learning, this is only equivalent to 11.2 years, leaving a learning gap of 2.4 years. How could this gap be closed? Are there specific areas of activity in your context that may be contributing to this gap - how might you address them?

- What systems, programmes or strategies do you have in place to address the wellbeing of your school or kura? Staff and students? Do they take account of cultural diversity in your community? Who contributes to wellbeing?

-

Links

The World Bank | Human Capital Project | Pillars of the Human Capital Project

This site explains the Human Capital Project with video, interactive graphs and data and key reports.

Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand | Mauri tū mauri ora | Wellbeing

This page describes five actions that can be introduced into your daily life to improve mental wellness. There is also a ‘Five Ways to Wellbeing at Work’ toolkit.

Ministry of Education | Changes In Education | Digital Technologies and Hangarau Matihiko learning

A detailed explanation of how the NZ National Curriculum has been adapted to now include Digital Technologies learning.

Market Business News | What Is Human Capital? Definition And Meaning

-

Papers