Understanding success

What's this all about?

For the last two decades “evidence-based decision-making” has been a mantra for policymakers, politicians and influential media. What is measured matters. Policy-makers, educators, parents, and the public want to know if our schools are successful; they want evidence of what is working well and where the education system is falling short.

PISA states in their Handbook on Global Competence:

“Every school should encourage its students to try and make sense of the most pressing issues defining our times. The high demands placed on schools to help their students cope and succeed in an increasingly interconnected environment can only be met if education systems define new learning objectives based on a solid framework, and use different types of assessment to reflect on the effectiveness of their initiatives and teaching practices. In this context, PISA aims to provide a comprehensive overview of education systems’ efforts to create learning environments that invite young people to understand the world beyond their immediate environment, interact with others with respect for their rights and dignity, and take action towards building sustainable and thriving communities. A fundamental goal of this work is to support evidence-based decisions on how to improve curricula, teaching, assessments and schools’ responses to cultural diversity in order to prepare young people to become global citizens.“

Traditional ways of measuring success - personally and as a nation - are often linked with economic outcomes, and social status. In a world where these may no longer hold value, we need to consider new ways of thinking about success. We need to broaden the definition of school/kura success by expanding the indicators used to measure progress towards that goal.

Many of the current local and international approaches to measuring and reporting on educational quality have tended to be limited to literacy, numeracy and science achievement. These measures are necessary but not sufficient. A growing chorus of voices is asking, “Isn’t education about more than that? Don’t we need healthy kids who can think; who are innovative and will grow up to be engaged citizens?” When there is too much emphasis on narrow goals, important priorities can be overshadowed.

The national curriculum mandates a competency-based approach. Competency-based assessment is a process where the teacher/kaiako works with the learner to collect evidence of competence, using the criteria provided in the assessment brief or in the national qualifications. It is not about passing or failing a candidate; evidence collection is more than just setting a test.

The New Zealand Curriculum defines key competencies as "capabilities for living and lifelong learning" (p.12). Using "capability" makes us focus on what students / ākonga are capable of doing and becoming, and how they use their understandings/knowledge, skills and values in particular learning contexts. This has implications for how we think about the types of learning experiences that will really stretch students as they encounter purposeful key competency/learning area combinations.

Our understanding of some common approaches to measuring success, used in New Zealand and elsewhere, are summarised in this table. In most cases these are all represented in the approaches taken to developing curriculum, but often one may be more dominant than others:

| Definition | Success measure(s) |

|

1. Skills |

Can the particular action be repeated to an acceptable standard within the same set of constraints?

|

|

2. Knowledge |

Demonstrating engagement with and understanding of various facts, information, descriptions etc. Including transfer and application to other contexts.

|

|

3. Capabilities |

Demonstrating deep-rooted ability which can be applied in many contexts.

|

|

4. Social Action |

Are there long-term, sustained benefits for both individuals and wider society?

|

Most schools, regions or nations are likely to use a combination of the approaches described here; the important thing is recognising where there may be a greater emphasis, and where particular characteristics are not being addressed.

For example, an over-emphasis on skills and/or knowledge at the expense of developing capabilities and transferring that into social action is likely to produce young people who are not adequately prepared to face the challenges ahead. Conversely, a programme focused on social action projects without ensuring the development of key skills, or the ability to engage with information and knowledge, may mean students have a well developed sense of social responsibility, but lack the foundational skills and knowledge to be able to do anything about it.

But how do we measure success across all four categories? For the first two the answer is reasonably straightforward, as we have had measures for skill development and knowledge acquisition in our traditional education system for more than a century. The challenge looms when we consider how we might measure success in the third and fourth categories, where the kinds of observable, ‘testable’ measures cannot be applied in the same way, and where evidence of development may occur across longer time periods than a single academic year.

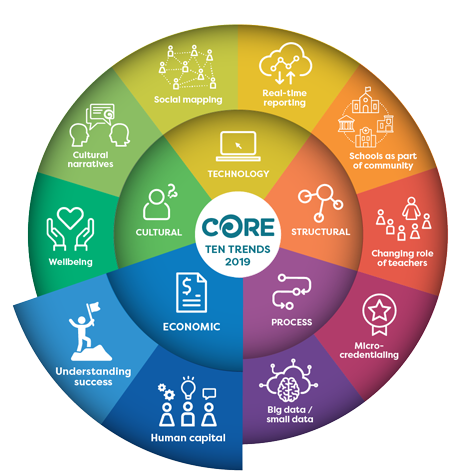

What's driving this change?

The following drivers are key to this trend:

1. Social/political

As the nature of work is changing, so too is what it means to be a member of a society where you may no longer just work as one of the crowd, conforming and carrying out routine and repetitive tasks. Greater diversity in the workforce means individuals are more likely to exercise their individuality in the choices they make about where they live, how they live, and who they vote for. The neo-liberal agenda that has emerged as a driver of this change over the past two to three decades has benefitted many, and disadvantaged many more. The resulting rise in inequality presents a challenge to our traditional social mores, and to the notion of democracy itself. Governments are increasingly interested in measures of success relating to the notion of citizenship, together with the desire to remain competitive in an increasingly global economy.

2. Environmental/future focused

As the global population increases we face problems of a scale and consequence never previously experienced. The impact of large numbers of people on the planet, driven by a ‘consumer’ mentality, has led to significant issues such as global warming, global food shortages, shortages of fresh water and so on. As Albert Einstein is quoted as saying, “we cannot solve the complex problems we face with the same level of thinking we had when we created them.” A key driver now recognised by many nations, as well as various global agencies and organisations, is that the solution to these large-scale global problems lies mostly with the changed attitudes and behaviours of every citizen, and only in part with the actions of governments and global organisations.

3. Economic

The exponential rate of change impacting the future of work and how we create and distribute wealth in our society is a key driver here. The traditional view of schools as places that prepare rangatahi / young people with a fixed set of skills and knowledge in preparation for their future careers is no longer valid. Industries and organisations are increasingly looking for people who demonstrate a wide range of capabilities that will enable them to adapt, to problem solve, to communicate new ideas, and to work in teams ahead of more traditional sets of skills and knowledge.

What examples of this can I see?

The following examples are selected to provide insights into the range of ways organisations are approaching the issue of measuring success:

- The Curriculum Progress and Achievement Ministerial Advisory Group (MAG) has recently published a conversation document in which the section on building assessment, inquiry and evaluation capability (p.16) states that all stakeholders will have the assessment information and evaluative capabilities they need to do their jobs well and we will have achieved a stronger focus on student progress across the system through rich opportunities to learn.

- The Minister’s foreword in the Digital Technologies - Hangarau Matahiko addition to the Technology learning area begins with “New Zealanders are now living in a digital society. Our young people need to be confident and fully equipped to contribute and flourish in the economy of the future.” The development of this curriculum content was driven to a large extent by industry requiring more young people to be prepared with future focused skills.

- The OECD is now focusing attention on the development of capabilities. They define global competence as the capacity to examine local, global, and intercultural issues, to understand and appreciate the perspectives and worldviews of others, to engage in open, appropriate, and effective interactions with people from different cultures, and to act for collective well-being and sustainable development.

- In an open letter to the New Zealand public, 100 NZ companies including Xero, ASB, Noel Leeming, Vector, and SkyCity, have said they would be more open to hiring those without tertiary qualifications to fill vacancies.

- Micro-credentials are becoming mainstream in New Zealand, with NZQA recently implementing a process for approving these on the qualifications framework. In a press release on this Minister Hipkins states “Maintaining up-to-date skills will become an increasingly important way to improve and future-proof employability” (August 2018).

- Triple bottom line (TBL) accounting is a practice being embraced by many companies. TBL is a concept that broadens a business' focus on the financial bottom line to include social and environmental considerations.

- An increasing number of schools are implementing strategies to involve students themselves in the process of assessing their work and providing evidence to support that - for example, Stonefields School Sharing Progressions with learners.

How might we respond?

In our educational institutions we must think about how our curriculum and assessment strategies can be developed to address the range of skills and capabilities required for the future.

Thinking back

In order to fully understand what needs to change in our system, and where we could focus our effort we should consider the following questions:

- What is happening in your context? What have the vision and values of your school been until now?

- Have you provided opportunities for your students to “be” this vision?

- How have your assessment practices supported you to know whether you have provided these opportunities, and that students are confident connected actively involved lifelong learners?

- Why was the assessment carried out that way?

- What uses were intended for the assessment information gathered? What uses were actually made of it?

- How effective have these approaches to measuring success been in preparing young people for their future?

Thinking forward

Increasingly, educators, policy makers and governments are responding to a need to consider a broader set of goals that address, for example:

- academic achievement

- physical and mental health

- social-emotional development

- creativity and innovation

- citizenship and democracy.

When thinking about what it means to measure success in terms of the investment we’re making in our young people think about:

- which of the areas above are your current approaches to measuring success addressing?

- what you could do in the coming year to develop learning opportunities that address those areas not identified, and what measures of success might you use to provide assurance that these things are being developed.

Consider the four dimensions of the chart in section one. Which of these four areas dominate the assessment thinking in your context? Why? What practical steps could you take to address the others?

-

Links

Battelle is a global research and development organisation committed to science and technology for the greater good.

A slideshare explaining UNESCO’s Four Pillars of Learning, a proposed integrated vision of education used as a basis for policy debate towards the notion of lifelong learning.

OECD PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) | PISA 2018 Global Competence

A resource with downloadable frameworks which include curriculum content domains and student competence questionnaires.

NPDL (New Pedagogies for Deep Learning) | The 6 C’s

A site explaining New Pedagogies for Deep Learning and a brief description of the 6C’s.

Ministry of Education | The New Zealand Curriculum Online | Key Competencies

This website has video, research papers, tools, examples and resources around the Key Competencies.

Ministry of Education | The New Zealand Curriculum Online | Reviewing Your Local Curriculum

A guide to local curriculum packages of support including workshops, guidance, design tool and links to curriculum, progress, and achievement emerging ideas.

The Ministerial Advisory Group sharing the six big opportunities for NCEA. Each opportunity is unpacked with a range of video, text and focus questions.

OECD | Public Employment and Management | OECD Report on Skills and Capacity

Ministry of Education | TKI - Te Kete Ipurangi | Science Capabilities in the NZ Curriculum

The five science capabilities explained.

Ministry of Education | Technology in the New Zealand Curriculum

The revised edition of the Technology learning area which now includes the positioning of digital technologies in the New Zealand Curriculum.

-

Article

Getting Smart | New Zealand Leads the Way on Competency-Based Learning: Part 1

A rich blog post that shares research for competency-based learning.

-

Research

This downloadable booklet includes a building capabilities framework on page 3 with two useful sections within the framework: what the teacher does and what the student does. It also describes the capabilities, their links with the Key Competencies, and how they are developed.

-

Readings

This is the global competence framework booklet referenced in the explanation.

-

Papers

Broader Measures of Success | Measuring what matters in Education

A project Initiative paper to identify a broader set of goals for education.

Automation and artificial intelligence | How machines are affecting people and places

An in-depth report and analysis that aims to clear up misconceptions around automation and (AI) artificial intelligence. It also looks back at the impact of automation and looks forward to the coming trends as they affect both people and community.

This paper explains why the science capabilities were developed, what they are supposed to do in terms of teaching and learning, and how they fit with the Key Competencies.

This document from the Ministerial Advisory Group describes emerging ideas and what they are intended to achieve from their review in 2017.

Ministry of Education| Digital Technologies | Hangarau Matihiko | Draft for Consultation

-

Video